Capitalism is in crisis. Riots sweep through London and protestors occupy famous public spaces. An Old Etonian Prime Minster struggles to steer the country through an economic depression while vast sums are spent for the Jubilee celebrations of an elderly queen. There are concerns about crime and rising immigration. The Metropolitan Police is under pressure and morale is low. Talk of revolution is in the air.

We could be talking about recent history – but this description also applies to the late 19th century. It was a time when Britain effectively ruled the globe, economically, politically and culturally. At its heart was London, the symbolic centre of the world.

The Victorians tackled the problems of their society by moving towards what was then dismissed as ‘state socialism’ – government intervention to help the poorest and most vulnerable. Trade Unionism was on the rise and in 1900 the Labour Party was formed. And in 1906 the Liberal Government brought in health insurance and the old age pension.

Now we seem to be going into reverse, cutting benefits and opening up the health service to competition in an attempt to save money. So should we dismantle the expensive welfare state built up over the last hundred years? And if so, are we in danger of returning to the hideous inequalities of the Victorian era? Can we learn anything from the crisis of the 1880s?

London then and now – Fleet Street from David Perdue’s Charles Dickens Page

Recession

Then: The ‘Great Depression’ began in 1873 with a European stock market panic and allowed the US to overtake Britain as the world’s leading industrial power by the 1880s. Although historians now suggest it ended in 1879, to many at the time the country appeared to stagnate for more than 20 years until 1896. Britain’s overall share of world trade fell from about 33% in 1870 to 17% in 1913.

Now: This financial crisis began in 2007 and shows no sign of letting up in the near future. Our banks had to be bailed out by the government, the stock market plunged and the government debt now stands at more than £1 trillion – 85 per cent of GDP. And now people are talking about a ‘triple dip recession’.

Poverty

Then: In the 1880s there was a huge public outcry about the state of the poor in Britain and particularly in the slums of London. The East End of the capital was so notorious that the upper classes would go ‘slumming’ to see bare-footed children running about the dirty streets. In 1884 one company even offered guided ‘slumming tours’ of the area. Four years later the East End was again the focus as Jack the Ripper murdered a series of prostitutes in Whitechapel and Spitalfields. The researcher Charles Booth calculated that around 30 per cent of Londoners were living below the poverty line.

Now: Critics of the government claim the period of ‘austerity’, involving cuts to budgets and benefits combined with stagnant wages and rising food prices, threaten to plunge more people into poverty. In 2008/9 it was calculated that around 22 per cent of the population were living in poverty (incomes at under 60 per cent of the median). However, unemployment figures continue to fall – suggesting more and more people are finding work, even if it is only part-time.

Riots:

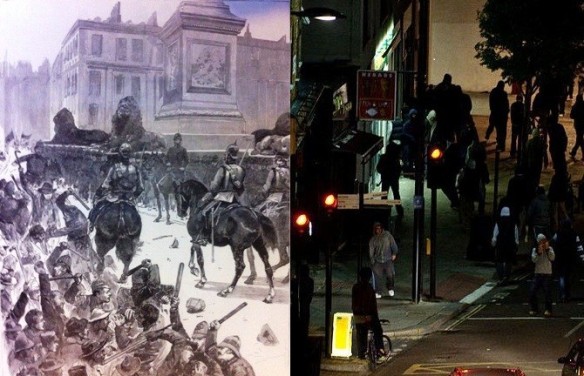

The 1887 Bloody Sunday riot in Trafalgar Square and rioters in Chalk Farm in 2011 (from hughepaul Flickr)

Then: The ‘West End Riots’ of 8 February 1886 saw a crowd of 5,000 unemployed and casual labourers go on a window-smashing rampage through the West End after a demonstration by socialist groups in Trafalgar Square. It caused such a scandal that the Metropolitan Police Commissioner had to resign. The unemployed and members of radical, socialist and Irish National organisations continued to gather in Trafalgar Square until in November 1887 the new Commissioner Sir Charles Warren banned public meetings there. The result was a clash between protestors and the police on 13 November, now remembered as ‘Bloody Sunday’, and 400 soldiers had to be called up to restore order.

Now: In 2010 students protested across the country after the coalition government proposed raising the cap on tuition fees to £9,000. On 10 November demonstrators clashed with police and smashed their way into Conservative Party headquarters at Millbank. Further vandalism took place in Whitehall and the West End on 24 and 30 November, and one protestor spray-painted Nelson’s column with the word ‘Revolution.’ A year later on 6 August 2011 the London riots broke after Mark Duggan was shot dead in Tottenham, north London, and spread to other cities including Manchester and Birmingham. Buildings were set on fire, shops were looted and rioters clashed with police in the streets.

Occupations:

Then: The homeless, unemployed and poor casual workers staged a virtual occupation of Trafalgar Square throughout 1886 and 1887 and the landmark became a focus for socialist agitators. One parade of the Socialist Democratic Federation on February 27, 1887, ended in a meeting in front of St Paul’s Cathedral. Thousands of demonstrators filled the cathedral and the surrounding areas with banners carrying slogans like ‘the wages of sin is death but the wages of the worker are slow starvation.’ Newspapers and magazines also took notice of the large number of Homeless people occupying open spaces like St James’ Park (see below).

Now: The Occupy movement spread to London in October 2011 when protestors set up camp outside St Paul’s Cathedral. They took up the ‘We are the 99 per cent’ slogan in reference to power, influence and wealth of the richest 1 per cent of the population. The group also staged protests at stores owned by major companies like Vodafone who are said to avoid paying their fair share of tax.

The Occupy protest at St Paul’s in 2011/12

Immigration:

Then: In the 1880s the main threat to British jobs, particularly in London, was believed to be posed by Jews fleeing from persecution in Russia. It was claimed that the unchecked influx of Jewish immigrants was forcing down wages and pushing out English workers. The Jews were also accused of setting up sweatshops, gambling dens, and other criminal enterprises. Arnold White, a campaigner and journalist, wrote that ‘England will cease to be England if our rulers do not show that they love the English more than the frugal, unlovable foreigner.’ Immigration controls were introduced for the first time with the Aliens Act of 1905.

Now: The 2011 Census has revealed that Polish is now England’s second language with 546,000 speakers in England and Wales. Fears of unchecked immigration, particularly from Eastern European countries, may explain the increase in support for the right-wing political party UKIP, who oppose the ending of controls on Romania and Bulgaria in January 2014.

The Queen’s Jubilee

Then: The first British monarch to have celebrated a Diamond Jubilee was Queen Victoria in 1897. Her Golden Jubilee in 1887 came just a few months before the Bloody Sunday riots and at a time of growing class conflict.

Now: 2012 was a time of celebration with both the Olympics and Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee. In June the Queen celebrated by overseeing a pageant on the Thames featuring hundreds of boats from around the world. The four-day extravaganza ended with a million people turning out to see the royal procession to Buckingham Palace. But the contrast between rich and poor was made clear by headlines such as ‘Queen’s Jubilee costs £3bn while the poorest starve’.

An Old Etonian Prime Minister

Then: Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, otherwise known as the Marquess of Salisbury, was the first Prime Minister of the 20th Century and was in power for most of the period between 1885 and 1902. He was a child of privilege – at five years old he was bounced on the knee of the Duke of Wellington and at 11 he was sent to Eton, where he suffered four years of merciless bullying before being taken out to be schooled at home. Oxford University was the obvious next step and at 23 he was elected to Parliament unopposed for the ‘pocket borough’ of Stamford. Salisbury was a natural Tory and an advocate of the free market, but by the 1880s he also supported gradual reform such as improvements in housing for the poorest in society – leading to newspapers suggesting he was in favour of ‘state socialism’.

Now: David Cameron gets a lot of flack for being an Old Etonian and member of the notorious Bullingdon Club – particularly after George Osborne’s famous ‘We’re all in this together’ speech. His background opens him up to criticism for being out of touch with the concerns of the ordinary member of the public. It doesn’t help that he is descended from King William IV through his paternal grandmother, and his mother is the daughter of a Baronet. Despite this, Cameron attempts to appeal to a wide section of the public and describes himself as a ‘liberal conservative’ and a ‘modern compassionate conservative’ – in 2006 he tried to soften his image with his ‘hug a hoodie’ speech.

Newspaper scandals:

Then: The ‘dead tree press’ was booming in the 1880s as newspapers attracted growing numbers of readers with tales of Jack the Ripper and other sensational murders. There were few tabloids in those days apart from the Pall Mall Gazette but that does not mean there was any lack of scandal. In 1885 the editor of the Gazette, W.T.Stead – perhaps the first ‘tabloid hack’ – published an investigation into the ‘white slave trade’, the sale of young English girls into prostitution across the world. Stead arranged to buy a 13 year-old girl from her alcoholic mother and had her drugged and taken to a brothel where he would pose as a prospective client. The scandalous story prompted the Government to pass a law raising the age of consent from 13 to 16. It also saw Stead jailed for three months for kidnapping and sexual assault. Then in 1887 The Times newspaper published a letter purporting to show a link between the murder of the Chief Secretary for Ireland and the Irish MP Charles Parnell. After an exhaustive 128-day government inquiry, it emerged the letter was a forgery and the Times was forced to pay £5,000 in damages and an estimated £200,000 in costs.

Now: The last few years have seen journalism come under fire for its harassment of celebrities and cosy links to the police and politicians. The phone hacking allegations first came to light in 2006 and five years later brought down the News of the World. Soon the foulest practices of the whole tabloid press were being aired on live TV at the Leveson Inquiry. And all this as newspapers slowly withered and died under the relentless pressure of instant online media.

Technology:

Then: In the 1880s Victorians were astounded by the new ‘electric light’ being used in some parts of London, Edison’s phonograph recordings of speech and music, and Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. The Victorian version of the internet was the telegraph, capable of sending messages quickly over long distances by copper cable. This was astounding to those who were used to waiting days, weeks and months to communicate with the rest of the world. But the real breakthrough didn’t arrive until wireless transmission was developed in the first years of 20th century, paving the way for radio and TV.

Now: The last twenty years have seen the emergence of something truly revolutionary – the internet. We now have phones that can take pictures, record video and sound, play music and download vast amounts of information at the click of a button or the swipe of a finger. Who can predict what life will be like in another 125 years?

Britain Overseas:

Then: The Second Anglo Afghan War ended in 1880 after 40,000 troops were sent to occupy Afghanistan and install Britain’s choose of ruler. Five years later General Charles Gordon was killed defending the city of Khartoum in Sudan (then a British protectorate) from Islamic Mahdi rebels. The fall of Khartoum was one of the reasons William Gladstone ‘s Liberal government collapsed to make way for Salisbury’s Tories. During the 1880s and 1890s Britain also fought in Burma, Tibet, Zanzibar, China (the Boxer Rebellion) and South Africa (the Boer War). At the time the British Empire was the envy of the world – although cracks were starting to appear.

Now: There are still 9,000 British troops in Afghanistan although there are plans to pull out by the end of 2014. Our armed forces are also still providing ‘military support’ in Iraq after combat operations ceased in 2011. Meanwhile the dispute over the Falksland Islands with Argentina continues.

Other tenuous comparisons (suggestions welcome):

The Cleveland Street Scandal of 1889 involved a homosexual brothel rumoured to be visited by Prince Albert Victor, grandson of Victoria and second in line to the throne. Today’s equivalent Prince William appears content with his marriage – but in August 2012 Prince Harry was caught naked on camera during a trip to Las Vegas...